By Kristen Hannum –

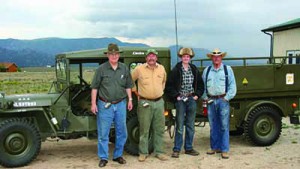

The electro Willys and its Juice Box park at home in Sangre de Cristo Electric’s territory.

In 2008, Arkansas River Valley resident Mike Picard bought a gasoline-powered Willys Jeep (vintage 1952) and put electric batteries into it. He also rigged a towable generator to enable the “electro-Willys” to go long distances, a hybrid of sorts with the 300-mile or so range of a gasoline-powered car.

Picard had hoped that his electro-Willys and its charging trailer would take part in the Military Vehicle Preservation Association’s 2012 4,000-mile Alaska convoy. But, Picard test drove them just before the convoy’s start and discovered that the Willys needed to go back in the garage for more work.

Picard had hoped that his electro-Willys and its charging trailer would take part in the Military Vehicle Preservation Association’s 2012 4,000-mile Alaska convoy. But, Picard test drove them just before the convoy’s start and discovered that the Willys needed to go back in the garage for more work.

Mike wires the contactor that controls the high voltage power in his Jeep.

Lots more work.

The story of Picard’s dream and his Willys’ return trip from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to his Colorado garage is both inspiring and bittersweet; it’s about individual, backyard American ingenuity but also about the inevitable setbacks that come with new technologies.

In a way, it’s surprising that Picard is tinkering with batteries at all, since his love affair with combustion engines goes so far back. When he was in high school in Rockford, Illinois, his dad

helped him locate his first vehicle. They found an old Willys in a truck graveyard and towed it home. “Two friends and I stripped it down in one weekend,” Picard said.

Then came the much longer job of putting it back together. Picard succeeded and still owns the Jeep. Ellen Picard, his college sweetheart and now wife, was responsible for keeping it in the family: Picard nearly traded it in for a Willys wagon. Ellen talked him out of it.

The generator feeds power to the panel box on the right, then on to the charger in the back.

Picard was commissioned into the Army at the end of college, and eventually become an officer in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, doing design and project management. He transferred from active duty to active reserve as a captain in 1990, landing a job as a surveyor for the U.S. Forest Service.

After 9/11 he was called up, serving from October 2001 until March 2004. When he returned from Iraq, his old Forest Service position in Washington state had disappeared, but he landed a new job in Salida and he and Ellen bought a home in Sangre de Cristo Electric’s territory in the Arkansas River Valley. The 40-mile round-trip commute wasn’t too bad until the summer of 2008 when diesel fuel hit $5 a gallon.

“We had talked about looking at alternative energy, wind for the house, solar for the garage,” said Ellen. “Then when fuel prices started getting high, we started talking about electric vehicles. I was a little skeptical at first, but it was also really exciting.”

“We had talked about looking at alternative energy, wind for the house, solar for the garage,” said Ellen. “Then when fuel prices started getting high, we started talking about electric vehicles. I was a little skeptical at first, but it was also really exciting.”

Mike Picard’s electro-Willys and Juice Box are on display at the Dawson Creek, British Columbia, military vehicle show.

Picard decided to go electric — with a Willys, of course. “They’re mechanically simple,” he said. “So I thought it would make an interesting conversion.”

He’s not the only person in the do-it-yourself electric car conversion universe to choose a Willys, although most people settle on something more aerodynamic. Sports cars, for instance. Porsches and Volkswagens are especially popular because there are kits. Do-it-yourselfers also hesitate at the Willys M38’s mid- 20th-century technology, but it’s their weight that’s the real deal breaker.

Military vehicles ready to join the convoy are waiting for clearance from Canadian customs. No problems!

None of that dissuaded Picard. “From working with heavy equipment, I knew I’d need more power,” he said. “I’d need more batteries and maybe a higher-quality electric motor to counter the design’s inefficiencies.”

Picard’s collection of Willys didn’t include the right specimen for the conversion, so he went shopping. He found a 1952 Air Force Willys that needed body work. “It had all the right things wrong with it,” he said.

He cleaned it up but didn’t disassemble the engine as he typically would have. Instead he decided to go with an electric car conversion outfit in Salida. A team there said it could do the conversion to lead acid batteries for just a couple thousand dollars.

The complications started almost immediately. The young mechanics wanted to install a direct connection between the motor and the transmission, and they thought the transmission should have just three gears instead of four. There are a thousand feet of difference between Picard’s home and his office, so he was leery.

Still, the crew had the Willys running by Thanksgiving. It topped out at an underwhelming 30 miles an hour. The crew had promised Picard he’d be able to go 50 or 60 miles on a single charge so that he wouldn’t have to plug the vehicle in at work, but it could only go 25 to 30 miles. “There were times, if I were fighting a head wind, that we’d barely make it home,” he said.

By Christmas 2008, he’d pulled the plug on the Salida crew. As he became more knowledgeable about battery conversions, Picard also grew more worried about the Salida team’s lack of concern regarding electrical safety. Its design stored 23 kilowatts in a battery pack consisting of 18 eight-volt batteries, but there was no way to shut off the power except for one on-off switch. “Contactors have been known to fail,” Picard said. “They’ve been known to fail welded shut so that the power continues.”

By Christmas 2008, he’d pulled the plug on the Salida crew. As he became more knowledgeable about battery conversions, Picard also grew more worried about the Salida team’s lack of concern regarding electrical safety. Its design stored 23 kilowatts in a battery pack consisting of 18 eight-volt batteries, but there was no way to shut off the power except for one on-off switch. “Contactors have been known to fail,” Picard said. “They’ve been known to fail welded shut so that the power continues.”

Worse, the 2008-era contactor controllers that the Salida team had used weren’t up to Picard’s safety standards. “It was the infancy of that part of the industry,” Picard said.

Mike washing the Willys before a car show.

If a controller and contactor failed, the next stop for a surge of electricity would be the motor, which would then destroy itself by spinning too fast. “What if I get into an accident?” Picard asked himself. “How can I immediately shut off the power?”

Picard fell back on his standard operating procedure: safety first. He disassembled everything and reassembled it. He installed a circuit breaker between the battery pack and the contactor. He jacketed all the small wires with a plastic loom to protect them from rubbing against the steel body. He used rubber grommets to keep wire from being in contact with steel.

Picard entered Electric Vehicle Television’s do-it-yourself electric vehicle contest, a showcase for innovative technology. When the contest judges announced the winners in 2011, Picard won second place out of 955 entrants.

His Willys’ unique conversion — with its towable generator — continued to stump Picard with a hundred puzzles. Delays in product deliveries for needed parts meant he couldn’t adequately test everything before the August 4, 2012, start date of the month-long Military Vehicle Preservation Association’s Alaska Highway convoy.

The nearly 100-truck-long convoy, beginning in Dawson Creek, British Columbia, celebrated the 70th anniversary of the building of the Alaska Highway in 1942.

The route also included the Top of the World Highway, the Denali Highway, the Dempster Highway (which crosses the Arctic Circle) and others.

Picard was in charge of fueling logistics.

That wouldn’t have been much of a job if the convoy’s route went down the East Coast, but Alaska’s outback is entirely different. There are stretches with 230 miles between gas stations. They would stop in eight communities over the month-long planned route that had only one fueling station. One place hadn’t sold gas for a year. Picard needed to guarantee 2,500 gallons of gasoline and 1,500 gallons of diesel at each stop. “That could wipe out a gas station if they didn’t schedule a delivery in time to support us,” he said.

That wouldn’t have been much of a job if the convoy’s route went down the East Coast, but Alaska’s outback is entirely different. There are stretches with 230 miles between gas stations. They would stop in eight communities over the month-long planned route that had only one fueling station. One place hadn’t sold gas for a year. Picard needed to guarantee 2,500 gallons of gasoline and 1,500 gallons of diesel at each stop. “That could wipe out a gas station if they didn’t schedule a delivery in time to support us,” he said.

The logistics ate even further into Picard’s compressed time window for testing his electro-Willys and generator trailer.

Like many participants, all of whom would be driving retired military vehicles in the convoy, Picard didn’t drive but rather hauled his Willys to Dawson Creek. He also transported the towable generator. He and three friends had an idyllic drive north from Nathrop up into British Columbia, the Willys and generator riding along.

Then, in Dawson Creek, on August 3, the night before the convoy was set to leave, Picard took a final test drive. Two terminals on the electric motor fried themselves within a half second on that drive. There was a short circuit on one of the cables that delivers power from the controller to the motor. The terminal short-circuited against the motor housing, destroying the insulator on the terminal on the motor.

At first, Picard thought he could fix the problem, but he soon realized it was a lost cause without new factory-designed terminals. “I couldn’t repair it with what I had with me,” he says. He sadly parked the Willys in a pasture and caught up with the convoy in the support truck. “The three guys who were with me worked hard to cheer me up,” Picard said.

Other convoy members were supportive as well, offering Picard rides on their Willyses, a dubious gift on cold rainy days since the Willys is open with minimal suspension on rough, corduroy roads — that is, roads made of logs covered with gravel and insulation, a defense against the summer mud and road heaves from freezing.

“I’ve driven a lot of that road, so I know what it’s like,” said Lorena Knapp, a medivac helicopter pilot based out of Soldotna, Alaska. “It’s not a great road.”

Locals, including Knapp, cheered as the military vehicles paraded through their vast backyard. The convoy had stopped at Knapp’s sister’s lodge, parking on an old runway. “It was a wet, drippy day, but they were out there having a fantastic time,” Knapp said. “They’re piling out of their vehicles, some of them are muddy, stepping down from open Jeeps. That couldn’t have been fun, but it was fun that we were waving from the parking lot.”

A couple dozen neighbors and about the same number of guests at the lodge shared cookies and coffee with the convoy participants, inspiring Knapp to blog about how passion can be infectious. “Are old military vehicles my thing?” she wrote. “Nope. But enthusiastic, passionate people living a Big Life are definitely my thing.”

When he got back home, Picard repaired the broken Willys. He pulled out the motor and replaced the two fried terminals, and it’s now a good commuting vehicle.

When he got back home, Picard repaired the broken Willys. He pulled out the motor and replaced the two fried terminals, and it’s now a good commuting vehicle.

He’s still working on the charging trailer. “My own experimentation has shown that the charging trailer can work if you solve a few basic problems.”

The technology is moving quickly, helping solve problems. The lithium ion batteries he’s now using, for instance, weren’t available in 2008.

Installing the windshield on the electro-Willys.“It’s been an exciting process to watch,” Ellen said. “There are a lot of people out there, doing their own thing. I’ve been amazed by the forums he’s joined online. He’s learned a lot, and has been able to share what he’s done with the technology.”

Ellen’s a website designer and has taken notice of the role the Internet has played, making it possible for the electric car community to help one another.

“We’re working on the great transportation movement of this century, as technology grows,” Picard said. “Early in the last century, all kinds of bicycle and wagon shops began building cars. Now we’re looking at a different mode of transportation and putting it together. It’s bringing electric cars back into the forefront.”Mike and Ellen Picard at the 2011 Rocky Mountain Airshow in Broomfield.

“We’re working on the great transportation movement of this century, as technology grows,” Picard said. “Early in the last century, all kinds of bicycle and wagon shops began building cars. Now we’re looking at a different mode of transportation and putting it together. It’s bringing electric cars back into the forefront.”Mike and Ellen Picard at the 2011 Rocky Mountain Airshow in Broomfield.

Picard is philosophical about the ups and downs of being a do-it-yourself inventor — his version of the Big Life. “If I knew in 2008 what I know now, the conversion of the Willys would have been significantly different. The biggest thing is I would have done it myself. But I’d do it all again.”

Kisten Hannum, a Colorado native, is a freelance writer and editor living in Denver. This is her fourth story for Colorado Country Life.