BY KRISTEN HANNUM

It was June 1957 when Paul Villa of the semipro Greeley Grays hit the ball out of an unfenced field at Greeley’s Island Grove Park. The crowd cheered and then gasped as a speedy outfielder chased it into the traffic on 11th Avenue and was nearly hit, cars braking, drivers shouting, tires squealing. The visiting player wisely decided to surrender the ball to its fate on the street. Then he looked back and saw that Villa, who was quite a pitcher but not much of a runner, still hadn’t even reached first base. The fielder made another dash for the ball. He threw it hard back to a fielder, who relayed it to another, who threw it to yet another. Villa was at last wheezing in to home plate, his brother George waiting to congratulate him. The ball beat him in.

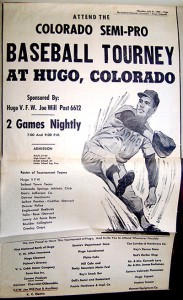

Paul was out by a mile,” Leo Carbajal told Jody and Gabe Lopez, who included the story in their book, From Sugar to Diamonds: Spanish/Mexican Baseball, 1925-1969. Those years included the golden age of American semipro baseball, between the world wars, when nearly every town in Colorado either had its own team or dreamed of fielding a team. They played a game profoundly different from the major league extravaganzas that people watch from the comfort of their air-conditioned living rooms today. “Today it’s win at any cost,” Gabe Lopez says. “Then they played for the love of the game.” Perhaps so, but the Grays also wanted to win, and an important part of this story is that the Greeley Grays became the team to beat. A team was important to community selfimage. And if that was true for Anglo communities, it was doubly true for Colorado’s Spanish-speaking, sugar-beet-field laborers that the Lopezes write about.

Beet field beginnings

The Greeley Grays started as the Spanish Colony team in the summer of 1925, playing other ballclubs from Greeley and the surrounding towns. The players’ wives packed picnics and everyone turned out for those games. “Whenever there was a baseball game, there was no one to be found in the It was June 1957 when Paul Villa of the semipro Greeley Grays hit the ball out of an unfenced field at Greeley’s Island Grove Park. The crowd cheered and then gasped as a speedy outfielder chased it into the traffic on 11th Avenue and was nearly hit, cars braking, drivers shouting, tires squealing. The visiting player wisely decided to surrender the ball to its fate on the street. Then he looked back and saw that Villa, who was quite a pitcher but not much of a runner, still hadn’t even reached first base.

The fielder made another dash for the ball. He threw it hard back to a fielder, who relayed it to another, who threw it to yet another. Villa was at last wheezing in to home plate, his brother George waiting to congratulate him. The ball beat him in. BEET LEAGUES SUGAR ColoradoCountryLife.coop April 2012 17 colony,” Gabe Lopez’s uncle Frank Lopez told him. Frank Lopez was one of nine Lopez brothers who played on the Greeley Grays, including Gabe Lopez’s father, Gus Lopez. The Spanish Colony team was one of several that had come together around the 13 colonies established by Great Western Sugar, a powerhouse grower of the early 20th century.

The fielder made another dash for the ball. He threw it hard back to a fielder, who relayed it to another, who threw it to yet another. Villa was at last wheezing in to home plate, his brother George waiting to congratulate him. The ball beat him in. BEET LEAGUES SUGAR ColoradoCountryLife.coop April 2012 17 colony,” Gabe Lopez’s uncle Frank Lopez told him. Frank Lopez was one of nine Lopez brothers who played on the Greeley Grays, including Gabe Lopez’s father, Gus Lopez. The Spanish Colony team was one of several that had come together around the 13 colonies established by Great Western Sugar, a powerhouse grower of the early 20th century.

The company had first employed Germans from Russia and then Japanese-Americans, but by the 1920s, 10,000 of Great Western Sugar’s 12,000 workers were Hispanic. The company recruited Spanish-speaking workers from southern Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Arizona and Mexico. Overcome by family needs back home, discrimination, and especially the lousy housing, those workers often quit their contracts before the season was over. Great Western Sugar bosses realized that decent, nearby housing would mean the farmers could retain their best workers rather than needing to chase them down every year. Great Western would offer low-cost sites and building materials to the most loyal and productive laborers.

The first adobe colony was established in 1922 in Fort Morgan; there would soon be hundreds across the West. Greeley’s colony, 5 miles outside the city proper, was platted in 1924. Weld County colonies in Ault, Eaton, Gilcrest, Gill, Hudson, Johnstown, Kersey, Milliken, Wattenberg and, of course, Greeley, all fielded baseball teams, at first sponsored by Great Western Sugar. In Greeley they learned the rules from Dimas Salazar, who had played softball in Walsenburg and came to the Spanish Colony in Greeley in 1925. Another of Gabe Lopez’s uncles, Alvin Garcia, was an 11-year-old batboy for that first team. By 1930 he was a 16-year-old baseball player. Garcia is “the father of baseball for the Mexican-Americans,” according to Frank Carbajal, another player interviewed by the Lopezes. It’s Garcia’s signature that establishes the Rocky Mountain Semi-Pro League, a league popularly called the Sugar Beet League, with the National Semi-Pro Baseball Congress.

Love of the game

That’s how baseball, the national pastime, became one with the beet field colonies. It was stoop labor in the beet fields all day, working the dusty rows of the broad-leafed plants, then the relief of running flat out on a ball field in the evenings and on Sundays, the only day that the workers had free for recreation. Boys dreamed of playing for their team. It didn’t matter that the ball they were playing with was homemade, of string and socks around a hard rubber heart salvaged from a store-bought baseball long since ruined. Their fathers practiced with balls that weren’t much different. They hit with cracked or broken bats, nailed and taped back together; they caught with mitts so meager and worn that the players called them tacos.

The earliest players made their own gloves of heavy canvas stuffed with rags. Like the other colony teams, they practiced on rocky land reclaimed from beet dumps. Home plate was a plywood square, and the bases were weighted sacks that the players would shove back in place after a slide. One of the old players, “Butter” Garcia, told Gabe Lopez that when he was junior high age in 1944, the Greeley junior high school’s team challenged the colony boys to a game and were routed. School in the colony ended at sixth grade, meaning the colony junior high-aged boys played baseball from morning to night.

The next game was between the town’s high school team and the colony kids, who won again but by a more respectable 10 to 4. If it cost money, that spelled the end for a colony player, including those recruited to play for high school teams. So they dreamed instead of playing for their own Spanish Colony home team, which in 1938 took on a new name: the Greeley Grays. “As soon as a child from the sandlot team was old enough to be a Greeley Gray, he was a Gray,” write the Lopezes. “The Grays became a team to be reckoned with.”

Semipro baseball important

Larry Gerlach, former president of the Society for American Baseball Research, says that semipro baseball was an important chapter not just of baseball history, but also of American social history. “Entire towns would turn out for games — men, women, children of all ages,” he explains. “It wasn’t just a baseball game going on, but a community gathering.” Gerlach, whose ancestors were German immigrants from Russia who worked in sugar beet fields in western Nebraska, also played semipro baseball. “The leagues were terrific,” he says. “We traveled around to the various towns and met people and had a great time.” Although some of the semipro players were paid (the definition of semipro is that at least one of the team’s players is paid something), the vast majority played for fun. The semipro teams were especially popular in the Midwest and West, says Gerlach, who today teaches the history of American sports at the University of Utah. “A lot of the things that would go on in these communities would be very ethnocentric — the language, the food, the religion but baseball, that was American.” Baseball became a fourth pillar of the community. It was like a church picnic, a school fair or a family reunion every Sunday all summer long. Babies slept on blankets in the sun and grandparents lounged in the cars. Families cheered and honked car horns. Kids chased each other and sometimes sisters with husbands on opposing teams would yell abuse at their own brothers-in-law, all to be forgiven after the game when everyone shared a meal. The other Weld County teams included the Milliken Caballeros, whose left fielder Ralph Solano told the Lopezes, “The only rivalry was when we were playing the game, but after the game we were friends; eating together after the game was like having a picnic with the other teams.”

From energy to history

Most of the Sugar Beet League teams had rosters with several brothers playing. There were several Carbajals playing for the Grays, for instance, along with all the Lopezes. Gabe Lopez’s father, Gus Lopez, was a star hitter. After moving to Cheyenne, he loyally drove his family back to Colorado on Sundays to play with the team. “We used to run around the parked cars on top of the hill in the parking lot of Forbes Field,” Gabe Lopez writes in From Sugar to Diamonds. “We ran after foul balls in the bleachers; the older kids got to stand and wait behind the irrigation ditch for home runs that were hit. The wives would lie out on blankets on the wooden bleachers so as not to get splinters as they jumped up and yelled at a good play or home run.” An old photo of Gabe Lopez shows up in the book; a small, serious-looking boy who is wearing a baseball cap and staring intently toward the camera. It’s easy to imagine that boy writing this book about the family team 50 years later. He already knew some of the stories — for instance, that his father had returned home from the war in Germany on a Tuesday in 1945 and played ball that following Sunday.

Good stories, to be sure.

But Gabe and Jody Lopez aren’t historians. How they came to write about the Sugar Beet League and become popular speakers with a traveling exhibit of approximately 185 artifacts, including uniforms, bats, balls and chalkers, has a dramatic history of its own. Gabe was a lead welder and journeyman fitter for Xcel Energy in Cheyenne, Wyoming, until 1995, when a terrible natural gas explosion at a nearby refinery left him disabled and in constant pain.

The Lopezes’ children, Kimberly and Mario, worried about their dad. What could he do to fill his days? They urged him to research their family history. That good-intentioned request led to two books, the first one, White Gold, on the history of Greeley’s Spanish Colony, and the second, From Sugar to Diamonds, about baseball. “They’re an extraordinary couple,” says Peggy Ford, research coordinator for the city of Greeley History Museums. The exhibit’s displays and photos track the Sugar Beet League’s evolution over the decades. By the time Gus Lopez played his last year in 1959, family cars no longer served as stands for the fans. The teams played on well-maintained fields instead of rocky, reclaimed beet dumps and used store-bought equipment. And then came television. Gabe Lopez says there were other reasons for the end of the golden age of semipro and minor league baseball. “The interest in community baseball died,” he says. “The whole dynamic of the 1960s and the early 1970s was against it.”

The Grays disbanded in 1969, but in 2005 something extraordinary happened. The Grays were reconstituted as part of the Colorado Collegiate Baseball League. Gil Carbajal, who played on the Greeley Grays from 1952 to 1967 and is a former trustee at the University of Northern Colorado, owns the team, keeping alive the tradition of one of Colorado’s most historic baseball teams.

Kristen Hannum, a Colorado native, is a freelance writer and editor living in Denver.